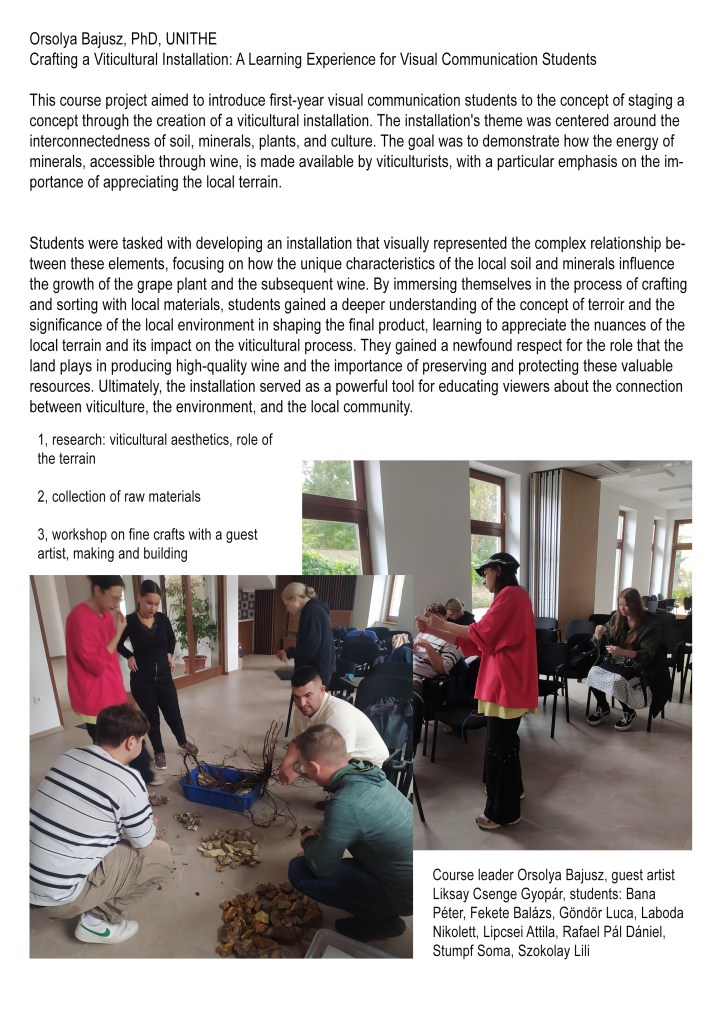

Látványtervek

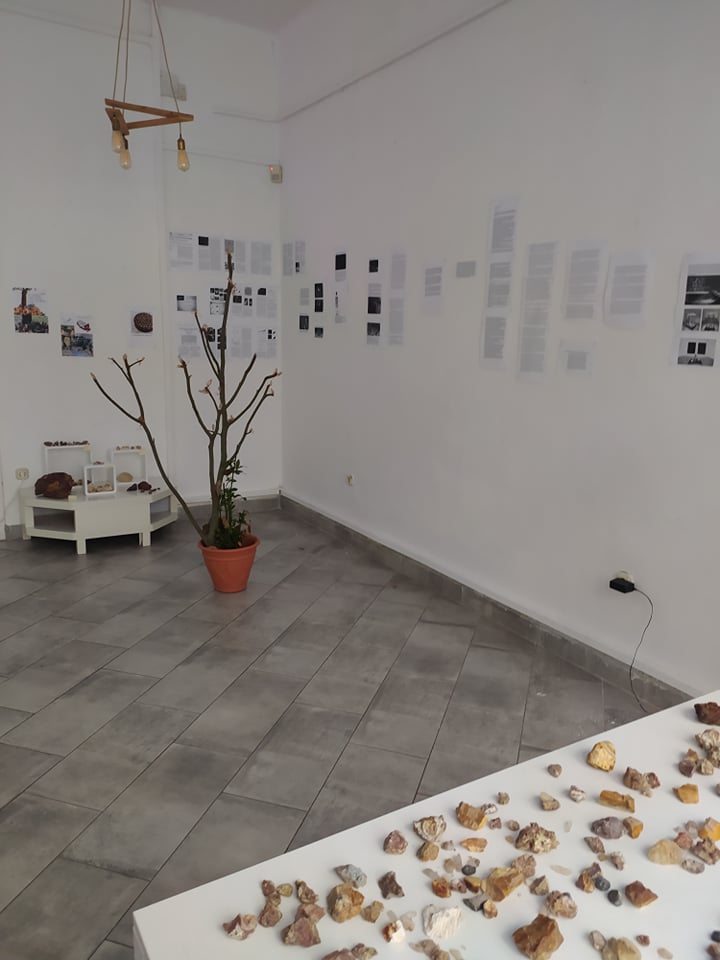

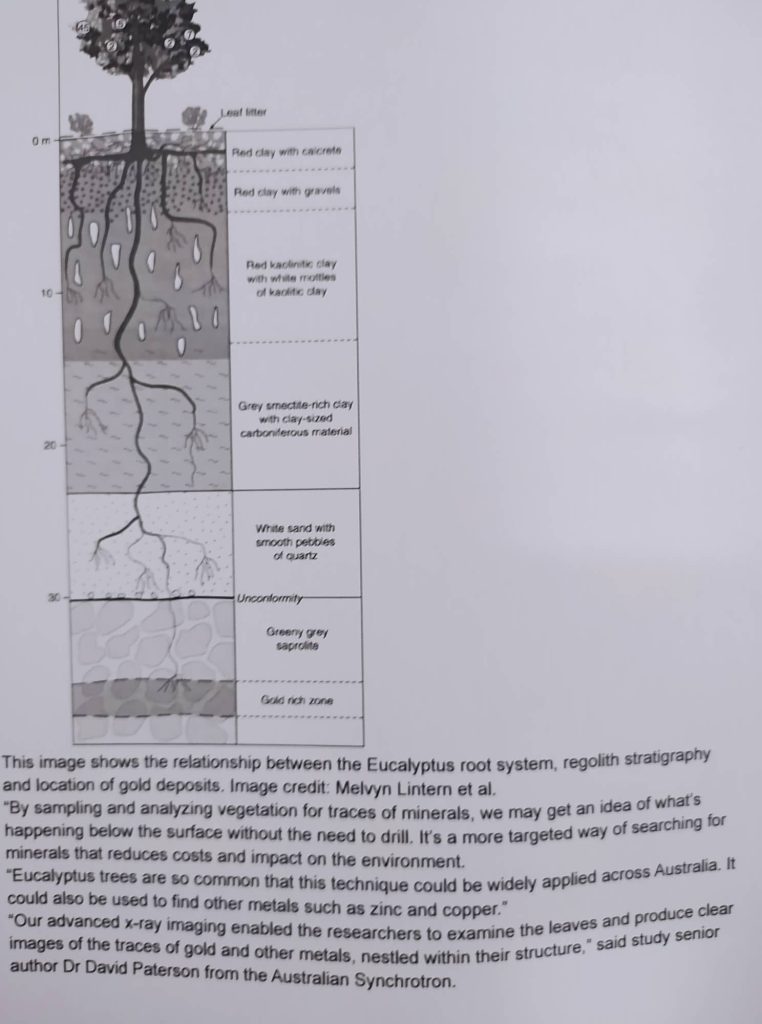

A geológia, a kövek, ásványok birodalma egyfelől fizika és kémia, másfelől misztérium. Mik is ezek a kövek? Az arany a földbe csapódott halott napokból van, az opál szilíciumdús oldat kristályosodva (ha üledékes akkor nyomástól), a mésző (kalcitok) ebből a földből van, ősállatok csontjai, az obszidián gyorsan megszilárdult láva- vulkáni üveg. A kövek működnek: a kvarckristály mechanikus energiát elektromos energiává alakít, a mészkő tényleg puha: a karsztvíz a mészkőben lágy víz, a vizek pedig az egyik mód kövekhez kapcsolódni. Az obszidián magától éles és steril, a zeolit és perlit szűrők.

A csodálatos obszidián (a térség első exportcikke) magától éles és steril

Obszidián pengékből installáció, amire gyümölcsök esnek, lefolynak, lerohadnak.

A csodálatos arany biokompatibilis, vagyis meg lehet enni.

Ezért a csodálatos arany a büfé étlapján lesz.

Arany sütiket kínáló büfé gyümölcsöskertben, körülötte az obszidán-installációk

vizualizálni, ahogyan a kőzetek energiáját a növények (és emberek) által feldolgozott víz közvetíti, vagyis a bor.

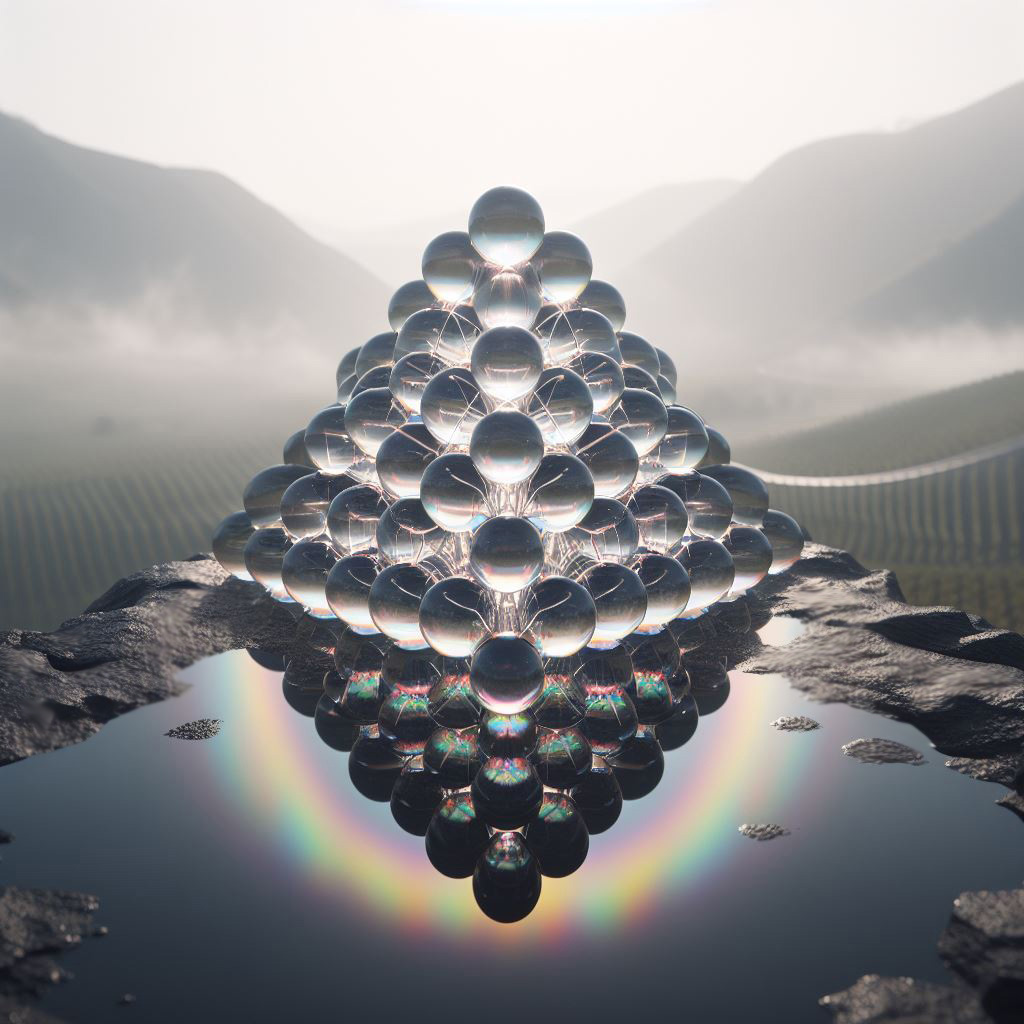

A csodálatos opál gömbszerkezete

Intalláció: üveg gömbök a szőlősorok között, ahogyan a nemesopál gömbszerkezete szabályos, a szabályosan rendezett gömbök is szivárványos fényt fognak visszaverni

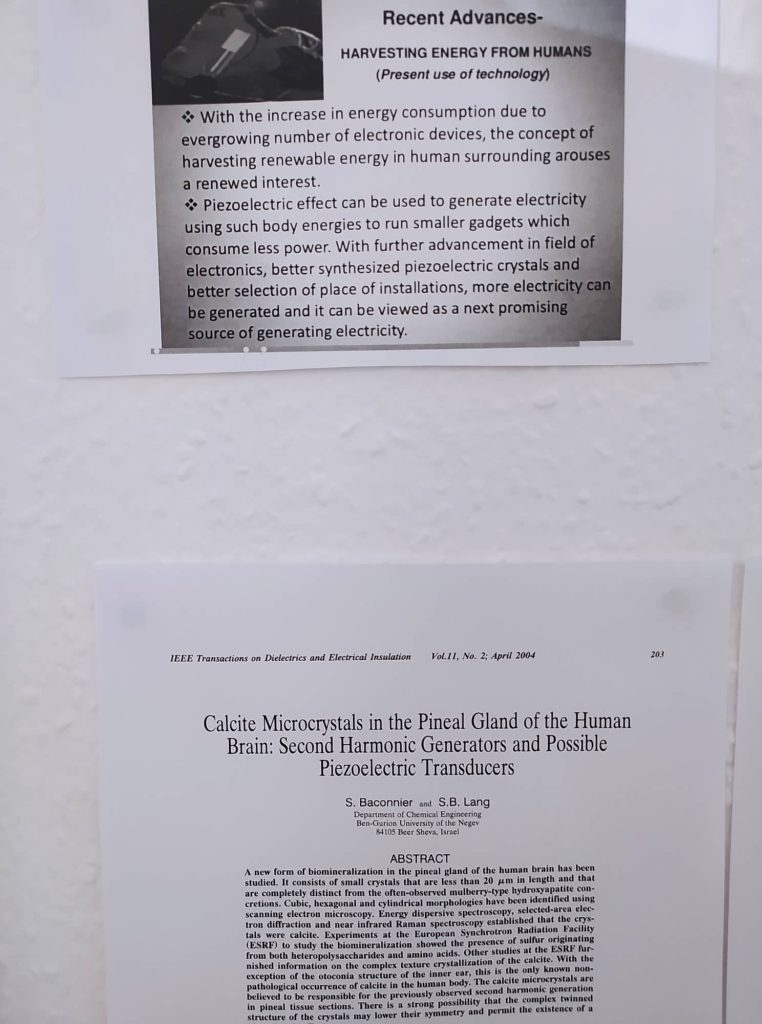

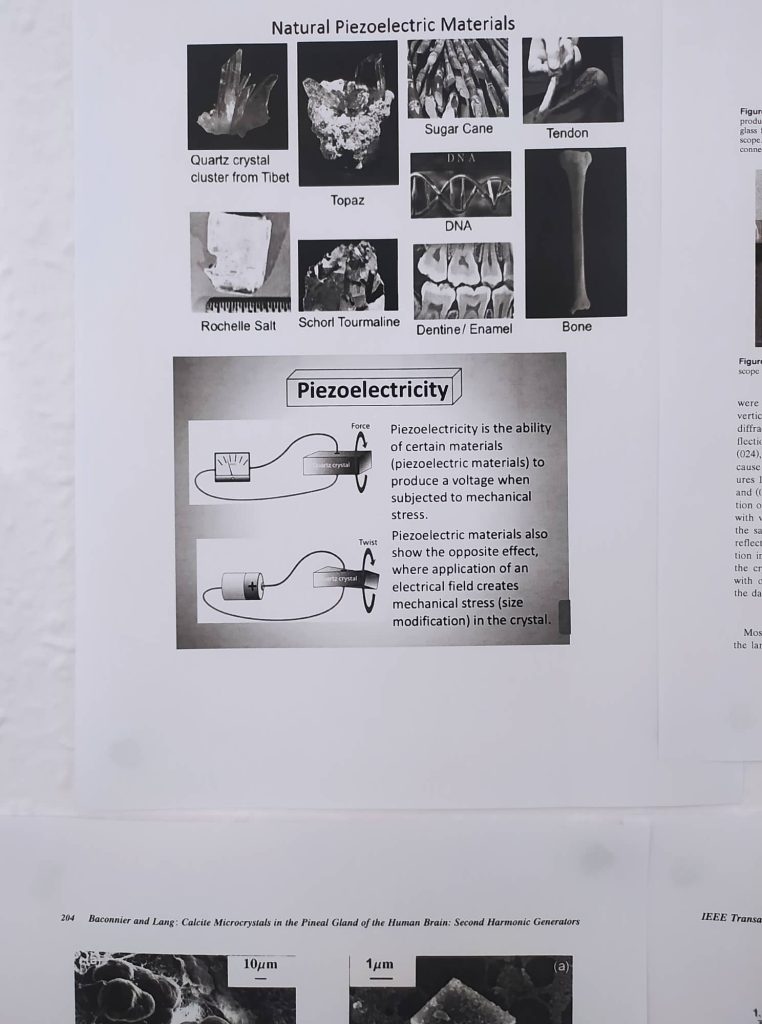

A csodálatos kvarc piezoelektromos, vagyis mechanikus energiát elektromos energiává alakít

Egy élő fa egy ágára szélcsengők kvarcokból, hozzájuk kapcsolva szenzorok amik a mechanikus energiával világítanak meg ledeket.

A csodálatos perlit a struktúrájában is, a felszínén is megköti a vizet

Szökőkút perlit struktúrával, élő növényekkel

A csodálatos zeolit ioncserélő szűrő

zeolit méhitató, élő méhekkel és mézzel

Installáció és konferenciaposzter a 2024-es Tokaj Wine Congress Programra

Első megjelenés a 2022-es Budapesti Tavaszi Fesztiválon a Bartók Negyed Art Clinic keretein belül.

A személyes motivációm:

Egy vietnámi étteremben voltam, 1200ft a leves a Gárdonyi téren. Egy nagyobb társaság, kb 8 fő ült a szomszédos asztalnál. A választási rendszerről beszéltek, hogyan fordította a NER a saját előnyére. Aztán egy nő arról mesélt, hogy van egy gyerekkönyv, amiben rókák magyaráznak asztrofizikát a gyerekeknek, misztikusan és absztraktan, de annyira, hogy ő sem érti. Nem kételkedik abban, hogy tudományosan stimmel a könyv, csak szerinte nem jó a gyerekeket “LESZOKTATNI A TUDOMÁNYOS, LOGIKUS GONDOLKODÁSRÓL”. Egy férfi rákontrázott, hogy nem két róka kellene, hanem egy nyúl és egy róka, és amikor a nyúl “elkezdene okoskodni, akkor a róka mondaná, hogy hamm bekaplak”. Magyarán erőszakkal kell elkussoltatni aki nem illik a világképükbe. A nő összemosta a tudományos és logikus fogalmát a mechanikus világképpel, pozitivizmussal, egyenes ok-okozati logikával. Nem kételkedett abban, hogy tudományos amit a könyv ír (“asztrofizikus írta”- tekintélyelvű magyarázat), de a gyerekeknek nem így kell gondolkozni. Azt mondta el a maga módján, hogy a gyerekeket a valódi tudomány logikájától kell védeni.

Egyénként aznap volt a születésnapom. Néztem őket, és arra gondoltam az életemben eddig minden szenvedést az ilyen emberek okoztak. Egy életre elegem van belőlük, semmiben nem vagyok hajlandó, és nem is fogok megfelelni nekik. Semmiben nem vagyok hajlandó kompromisszumot kötni ilyen emberek miatt. Ennek a jegyében születik ez a tanösvény.

Kontextus, a PHD-m bevezető fejezetéből:

According to Eurobarometer 340: ‘Science and Technology 2014’, there is much interest in science (over 80% of respondents), but only 10% of European citizens consider themselves well informed.

It is not my wish to return to the deficit view (that the public is ignorant), but to situate this gap between the public’s level of interest and their knowledge of science as part of a broader phenomenon: actual science is way beyond popularized notions about science.

Firstly, culture (a set of meaning-making practices, representations, and narratives) influences both the praxis and reception of science (Franklin 1995), but often what mass media and popular culture claim to be science are no longer scientific, (ie it is based on since falsified premises or negated evidence). Theoretical discourses expand very fast, and so does scientific and technological innovation, but the popular notion of ‘science’ (positivist, Newtonian, mechanical) is still different than the actual science which drives innovation and knowledge production.

If we look at contemporary developments within science, the core ontology and cosmology of the world has changed: considering the Earth to be a living entity (Gaia), claiming that everything material on it might have some form of consciousness (panpsychism) is now a legitimate branch of academic philosophy. Consciousness has no clear definition within cognitive science (or measurable unit), but at least it is a proven fact that matter is not fully dead – matter has self-organising properties as in the case of crystals, electronic circuits, or chemical reactions. As philosopher Manuel De Landa (2000) says from a new materialist perspective: “even the humblest forms of matter and energy have the potential for self-organization beyond the relatively simple type involved in the creation of crystals… … It is from these unlimited combinations that truly novel structures are generated. When put together, all these forms of spontaneous structural generation suggest that inorganic matter is much more variable and creative than we ever imagined. And this insight into matter’s inherent creativity needs to be fully incorporated into our new materialist philosophies.” (200:16).

Earth or matter might have some form of consciousness, but the discipline that ‘invented’ the human psyche is in a serious credibility crisis. Besides the failure to define and measure consciousness, academic psychology, especially social psychology, has a replication crisis (similarly to many other branches of academia). Due to failed replication experiments, we can even claim that any given finding in psychology is more likely to be fiction than fact. Out of 100 experiments published in 3 top-tier journals, only 36% of the replications were “successful” (i.e., produced p values < .05) (OSC 2015), and further experiments revealed a similarly low level of reproducibility (Klein et al., 2018, Camerer et al., 2018). One psychological phenomenon for whose existence we have replicable evidence is extrasensory perception (ESP). Daryl Bem has carried out a 10-year investigation with nine experiments, involving a thousand subjects, and, as a result, in 2015 and 2016 published a meta-analysis of all known replications conducted up to that point by thirty-three labs in fourteen countries: the overall result (albeit with a small significance) exceeded the criterion for decisive evidence.

At the time of writing the existence of ESP is more proven than the unreplicable findings of the Stanford Prison experiment (which would not even be ethical to replicate, let alone possible) or many popularly known social psychology “facts”. As of now, it is considered more scientific to say our (scientifically unapprehended) consciousness is part of a larger whole, than to claim each human harbors a dictator and a sadist within themselves, or ‘each to their own, or everyone is an island within themselves. We could say that the progress actually happening is more progressive (adds more to the wellbeing of every sentient being) than the past notion of ‘progress’.

The horizon of modernism was at the end a teleological axis: there used to be ‘a future’, but nowadays, besides the crises pertaining to liberal institutions, and political establishments (previously considered the endpoint of history), a climate disaster looms over any whatsoever future. There is no more ‘progress against ‘backwardness’, as this temporal axis has been lost.

Concepts such as the ‘enlightened West’ or ‘catching up’ have lost their appeal. With an economically, politically, and ecologically uncertain future, the loss of overarching visions about any future, now political mobilization and even community engagement is overarchingly based on moral appeals. It all happens in the here and now (for example social media providing a site for temporary mob formation, or instant gratification), there is no need to provide a vision, just moral positions to assume.

According to Eurobarometer 419: ‘Public perceptions of science, research, and innovation’ (2019), a large proportion of Europeans believe that science and technological innovation will have a positive impact on addressing most of the problems the society faces in the next 15 years. The 2014 Special Eurobarometer 340: ‘Science and Technology Survey’ shows that Hungarians are very interested in new scientific discoveries and technological developments (91 %, among the highest EU rates). 46 % of them disagree with the statement that “in my daily life it is not important to know about science”, while 36 % agree (the EU average is 48 % and 33 %, respectively).

On the contrary, public debates on science and technology are relatively low-key. For example, there was some media attention to GMOs (Vicsek 2014) but it was nowhere comparable in scale with the debates in the USA, the UK, or Germany. When the Hungarian media did publish about GM crops or their local introduction, it was usually from within the anti-GM threat frame (Vicsek 2014). Visual materials generally mobilise on this alleged danger and shift discourses towards populist tropes which are based on fear. There are claims in the literature according to which such visuals may have played a large role in obstructing the European introduction of GMOs.

However, the lack of public attention to GMOs is not an isolated case. The planned Hungarian acquisition of Palantir’s predictive policing technology (combining and analysing big data, including biometrics) received little to no media attention. During the 2018 Brain Bar Budapest, its founder, Peter Thiel visited Corvinus University, and no one paid attention, apart from a few ‘anarchists’ who told me about their plans to soak the event all over with pig’s blood (since Thiel is a ‘vampire’), but eventually, this plan fell through. In comparison, in the UK or the German press, Palantir was front-page news. Also, there was practically no public debate on CRISPR or the ethical issues of assisted reproductive technologies. Consequently, the countrywide implementation of a standard or that of technology is a political matter, inseparable from legislation and party politics. For example, GMO prohibition is part of the Hungarian constitution (article 20 paragraph 2) despite the scant media attention on GMOs or the relatively small popular backlash.

A factor influencing these debates (or their absence) is how they happen, where, by whom- and nowadays science communication increasingly employs novel media formats and resources (e.g. Lesen et al. 2016). A large part of the toolkit employed by such science communication, based on visual media and participatory methods is derived from contemporary art (participatory art, tactical media, performance), which itself increasingly loses its autonomy. This both means the popularisation of the toolkit of contemporary art, and the involvement and influence of other domains. Art has been separated from science and politics since antiquity, but now this is changing with media convergence (the interconnection of information and communications technologies, computer networks, and media content) and the increased extent of networking between various social actors. The entanglement of these domains (which in turn also fundamentally changes these domains) influences all social life. Studying novel formats of science communication can provide an insight into these processes. FORRÁS